Mary Kay For Millennials

How Glossier capitalized off of America's Democratic and Epistemic Crisis

*Hello! As I work through my debilitating writer’s block, I thought I’d share a vintage piece of writing on Glossier. In light of the release of Marisa Meltzer’s book -which I’ve yet to read - here’s my take on the brand that basically had my heart all throughout my college years.*

In September 2010, Emily Weiss launched a beauty blog called Into The Gloss, in 2014 she launched Glossier, and by 2019 the DTC beauty brand’s valuation reached $1.2 billion. Glossier took advantage of a burgeoning social disruption. A disruption precipitated by the internet, traditional media, and the 2016 United States presidential election. Trump leveraged Twitter and denounced news media as a strategic populist tactic to form a seemingly more authentic relationship with voters. At the same time, traditional media outlets were warning its audiences of the disinformation and misinformation being spread online. This led Americans into aimless rumination over who they could trust, what was fact, and what was credible. Eons before The Democratic and Epistemic Crisis, the beauty industry was (and largely remains) hard to trust. Incumbents have all touted their products as being the longest lasting, the most volumizing, and so forth. Glossier’s first four products consisted of an all-purpose balm akin to petroleum jelly, a moisturizer, a skin tint, and a facial mist. There were already thousands of these products on the market; some more affordable, some more luxurious, all more well-known with many backed by massive corporations and conglomerates. Weiss launched a line of cosmetics in an overcrowded and mature consumer category, yet headlines everywhere read “Glossier disrupts beauty industry.” Those headlines were right, though the brand’s success cannot be accredited to the creation of a better product, rather Weiss sought an ideological opportunity through The Democratic and Epistemic Crisis.

Cultural Orthodoxy: Makeup First, Skin Second

The cultural orthodoxy of the beauty industry seemed generally inert. Spots for makeup featured montages of beautiful women (usually celebrities) wearing the product, while they or an omniscient authoritative voice spoke to viewers listing off the specs and benefits. Makeup trends changed but the marketing and advertising of these products remained relatively stagnant. In the U.S., skincare had long been the ugly step-sister of makeup. Commercials usually targeted an older demographic of women whose concerns were the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles (think Norma Desmond archetype), or hormonal acne-ridden teenagers. The idea behind the skincare ads were purely reactive, the goal was to erase a pimple or wrinkle as opposed to the idea of taking preventative measures or as it would later be framed, caring for one’s skin. Advertising reinforced consumer expectations of wanting immediate results. Evident through Weiss’ blog, there was of course an interest in skincare as this ritualistic labor of love, but that interest was niche and hadn’t quite yet crossed the cultural chasm. Moreover, the advertisements for beauty products reflected the pharmacies, department stores, and Sephoras that housed them; visibly they were all red oceans! They all carried lipstick and they all promised the same results, virtually this was the case for every beauty product you could ever think of. This often resulted in consumers making purchases arbitrarily with very little affinity for specific beauty brands. Aside from opting for a product based on celebrity endorsements such as the Beautyblender® as prompted by Kim Kardashian, people weren’t really putting a whole lot of thought into their purchasing decisions. All major brands’ promises were indistinguishable and riddled with vague buzz words.

Social Disruption: IRL vs. URL The Democratic and Epistemic Crisis

The advent of the internet and of social media provided many affordances and possibilities. The major one being the democratization of information, humans around the world with access would write the internet, ultimately challenging an IRL epistemic hierarchy. In the spring of 2015, Donald Trump announced his candidacy for President of the United States and what followed was a mission to vociferate “fake news” into the cultural imagination. The weeks and months leading up to the 2016 election, I heard Americans and non-Americans expressing with conviction and mirth that Hillary Clinton was about to become the new leader of the United States. These people were ensconced in the echo chambers of their digital mediums. Amongst younger generations, there was a growing sense of disillusionment in conventional political systems. Online they rejoiced in the myth of direct democracy, their voice mattered and it was reflected in the number of people that all seemed to endorse shared values, be it liking a YouTube video in agreement with a majority that Nicki Minaj’s Anaconda is phenomenal or posting #notmypresident into the Twittersphere. The social disruption consisted of a growing disillusionment in authoritative figures and official channels of expert knowledge. As such more people began espousing digital media to engage in a participatory dissemination of information. Of course there are a slew of issues when it comes to not having a trusted organizational structure of expert knowledge; conspiracy theories run rampant and plague many minds leading to real-world consequences… like a man from North Carolina firing a semi-automatic rifle in a pizza restaurant. There was a major cultural tension that arose out of the de facto DIY online democracy and in the real world, America’s increasingly deficient democracy.

Ideological Opportunity: The Democracy Myth

As Emily Weiss was on the hunt for venture funding, she spoke to many investors about her idea for a DTC cosmetics line, out of a dozen only one was willing to invest. Glossier launched four products in 2014 with $2 million of funding. From 2015 to 2016 the toddler-staged company experienced 600 percent year-over-year growth. Weiss was featured in Forbes 30 under 30, Fortune’s 40 under 40, and in Time Magazine’s 100 Next. So how did this basic beauty brand that didn’t even offer in-person testing— which was ritual to buying makeup— become what some had dubbed the soon-to-be “Nike of Beauty”? The cultural orthodoxy of the mainstream beauty industry was authoritative, consumers bought products based on the knowledge of brand-appointed experts; these experts belonged to the rich, famous, and beautiful lifestyle. But people were growing tired of this aspirational rhetoric, people aspired for more immediate and attainable goals like paying off their student-debt, being able to purchase a house one day, and landing a job— that wasn’t working at Starbucks— in an increasingly competitive market. In essence, consumers were tired of inorganic messages shoved down their throats by people they could not identify with. The internet however was non-authoritative, it was widely accessible. Weiss took advantage of the social disruption, she spotted the power of ordinary voices online and built a billion dollar DTC brand. Through strategic copy, marketing, and product design, Glossier propagated itself as having ‘democratized’ beauty.

Source Material: Multi-level Marketing

My mother was brought up with the myth that the more money something costs, the better it was. During Thanksgiving I noticed my mom had bought dozens of beauty products by a brand called Arbonne; it was yet another multi-level marketing company comparable to Amway, Avon, or Mary Kay. Like most women, my mom is not attached to any beauty brand, however I was shocked to see the Arbonne containers, after all it was only a month prior that I had gone with her to purchase a new foundation, ultimately settling on Armani’s $80 Luminous Silk Foundation. Arbonne was cheaper, which went against my mom’s association of higher price with higher quality, and it wasn’t as well known as the Armani brand. I couldn’t rationalize her Arbonne purchase until recently. Companies like Arbonne had one important tactic that Glossier would adopt too, namely, that they used regular people to sell their products. It was social, it was someone you knew, it was someone you could trust. Of course Glossier’s consumers were not the same people that would buy Arbonne; Gen Z and Millennials weren’t going to host 80s style makeup parties in their living rooms with crustless cucumber sandwiches and Waldorf salad. Rather the kind of IRL social non-expert tactic used in multi-level marketing would be easily appropriated online: the URL was where younger generations were spending an increasing amount of time. Weiss hired 500 Glossier reps each with their own page on the company site, everytime the reps made a sale they got a product credit and monetary commission. Glossier saw every consumer as an influencer to their social sphere in the same way that multi-level marketing companies did.

Source Material: French Girl Beauty

To distinguish oneself from the autocracy of the American beauty industry, Glossier’s products needed to reflect different cultural codes and expressions. This is most evident in the brand’s name and its emphasis on the french pronunciation: Gloss-eee-yay. But Esther Lauter, who changed her name to Estée Lauder in order to sound more French, created her eponymous brand nearly 70 years prior. The massive l’Oréal and many of its subsidiaries had French names too; all of which became drugstore staples of the American beauty industry. These brands, however french-sounding they were, did not reflect the cultural codes that Glossier would exploit to their massive success. Glossier emphasized the French Girl Beauty myth, often thought of as an appearance that is created out of joy rather than necessity, it’s effortless and is presented as minimalist. These are products that French women buy at their pharmacies: Embryolisse, Nuxe, and Caudalie are top contenders. Adopting the French Girl Beauty Myth seemed like the perfect match for the brand’s mission to gather a promotional-army of virtual non-authoritative consumers. French Girl Beauty was an expression of body-positive feminism and it was about celebrating imperfections.

However Americans weren’t unhappy purchasing makeup or wearing it, they just didn’t exhibit brand loyalty because there was so much to choose from and all brands promised the same thing. As reflected in her blog, Weiss was interested in luxury skincare but this interest wasn’t mainstream. To become a successful American beauty brand Glossier had to appeal to American sensibilities; this meant creating a line of no-makeup but actually makeup cosmetics, something Starbucks had done in a similar way with coffee by democratizing artisanal-cosmopolitan codes. To make the French Girl Beauty myth attractive for American consumers Glossier blurred the line between makeup and skincare. For several years Glossier’s Phase 1 kit of products consisted of a balm, cleanser, and a tinted moisturizer; it was marketed as skincare but was actually a blend of makeup and skincare. For a long time the brand avoided using numbered codes for the shades of skin tones as this was heavily associated with foundation which often epitomized the consumer’s arduous attempt at finding the perfect match. Glossier also trademarked product names so that it wouldn’t be another lipstick in a red ocean of lipsticks, rather it was a Generation Z, blush was Cloud Paint, highlighter sticks were Haloscopes, etc… This is how Glossier created no-makeup but actually makeup. Glossier as a brand was littered with codes of the French Girl Beauty myth, they peddled consumers with phrases like “Skin First Makeup Second” and “Skin Is In”. Glossier consumers weren’t actually giving up makeup but it felt like they were because this new attractive lifestyle beauty brand divorced itself from the cultural orthodoxy of the beauty industry.

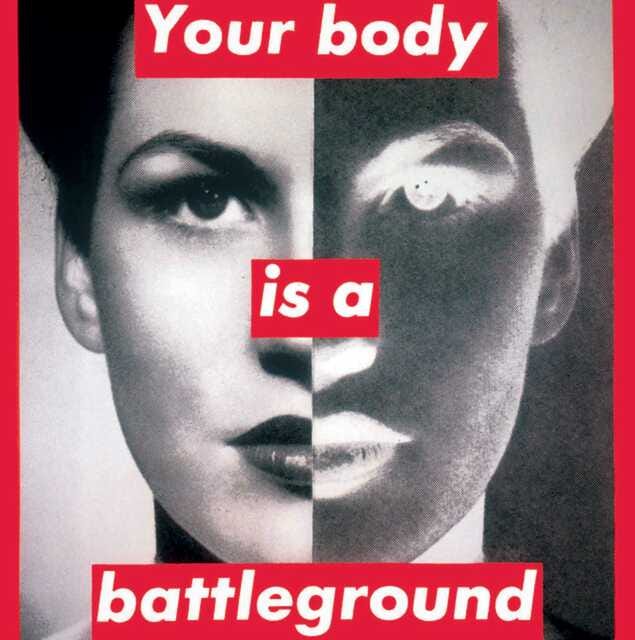

Source Material: Barbara Kruger

Artist Barbara Kruger is notoriously anti-consumerist, one of her most well-known works is an appropriation of Renée Descartes’ “Cogito Ergo Sum” into “I Shop Therefore I am”. And yet ironically her design aesthetics have been appropriated by some of the most profitable consumer brands, most notably the streetwear brand Supreme. Glossier used a similar font that Kruger does in many of her works, often overlaying it on a red block background as Kruger has done many times. Whether intentionally or not, Glossier’s attempt to be associated with Barbara Kruger is smart: Kruger despises consumer culture and her works often challenge misogyny and the objectification of women. Glossier was trying to dissociate those very aspects as well, by using Kruger’s design aesthetics Glossier sought to identify with the same ideologies associated with the art.

In an interview Weiss mentioned that she had asked consumers what product they would like to see next, and that many responded with products that did not even fall within the realm of the beauty category. I think this anecdote reveals a lot about Glossier’s success, specifically, that it had nothing to do with the products themselves...or at least not what was inside of them. What Glossier did differently was spearhead the democratization of beauty ideology. Their clever online ‘everyone’s an influencer’ marketing tactic as well as the cultural codes they used to express the French Girl Beauty myth is what actually disrupted the beauty industry. In the words of Weiss, “it takes a lot more than a great product to make a great brand”.